English Lesson in Advertising: An Authentic, Creative Atmosphere for Grade 10 Students

July 2020

Teacher Praew actively seeks ways to foster an authentic and creative atmosphere in her English classes. She wants her M4 students to feel that their class is a “real English environment.” Using original role playing tasks is one method for developing such an atmosphere. Drawing on her own inner resources, Praew discovers a range of engaging actions to connect with the students and simultaneously provide tools for learning English.

Teacher Praew actively seeks ways to foster an authentic and creative atmosphere in her English classes. She wants her M4 students to feel that their class is a “real English environment.” Using original role playing tasks is one method for developing such an atmosphere. Drawing on her own inner resources, Praew discovers a range of engaging actions to connect with the students and simultaneously provide tools for learning English.

Today’s M4 (Grade 10) class begins with five minutes of pair work, doing simple conversation to inquire briefly into others’ perspectives on advertising. “What’s the funniest TV commercial you’ve ever seen?” or “Why is it necessary to advertise?” With options projected on the big screen, students can choose from any of 16 questions, or make their own.

With all eyes to the front, the teacher boldly announces with her strong deep voice: “So today, you will sell your tour package!” She explains the day’s structure so that by the end of the double period, all students will have had a chance to hear all the others’ mini-sales pitches for an 1849 guided tour package from one destination to the distant mountains of the California territory where gold has been discovered in the water streams.

Hearing and seeing how other students approach the same task in different ways is an important element of developing mindful awareness.

How interested are these Thai students in the history of California? The prior lesson had introduced them to the rapid migratory history of 1848-1850 that made California into a state. As homework, students had already designed clever (and some artistically sophisticated) posters to seek out potential customers. Putting themselves into their 1849 characters, most were aiming to get rich quick, as they began to role play (without being asked) into the needy mindsets that had been set off by the discovery of gold in the river next to Sutter’s Mill in rural California. A few considered how to support the needs of families when traveling through the mountainous territories of the American wilderness.

As students sink into their new creative task, a list of words and phrases is put up on the screen to help them create their sales approach. Soon, a friendly tip is added: “Another thing: When you present, don’t read your lines because…think about it. If you read, how will your customers feel? So think of the key phrases that you want to speak.”

Giving students the opportunity to be creative was embedded in the role play lesson in two ways: First was the process of making an advertisement for selling a tour package, and all the ideas that come in the planning process. Second creativity was elicited by letting students pretend to be customers and the unexpected questions arising from them during an in-person sales pitch. Simultaneously, authenticity was elicited by several elements of the role play: 1) The feeling of what it means to plan a successful sales pitch; 2) customers asking questions while trying to decide which tour to choose; 3) the physicality of customers moving around the room, going from one place to another, like moving between travel agents on a street.

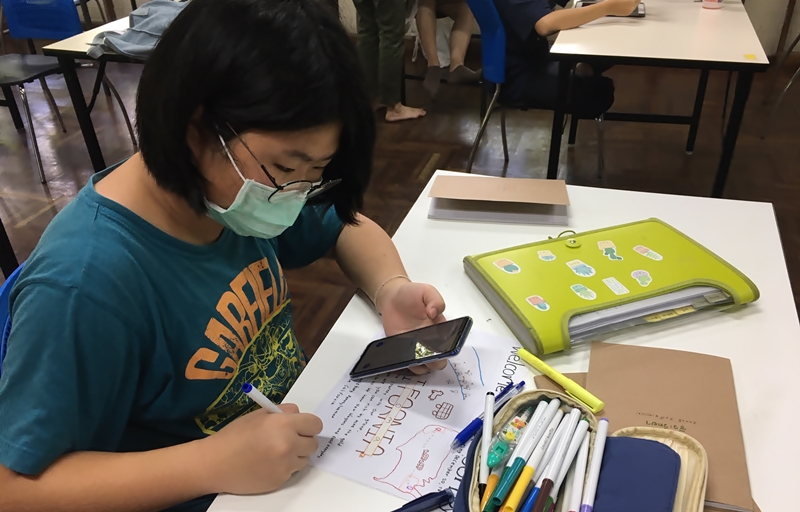

For about 20 minutes, students dig into their mobile phones as tools for looking up vocabulary, brainstorming ideas, jotting down notes on paper or in their devices, in tandem with Internet explorations. There is a humming sense of anticipation, a focus on finding or refining their use of the right words to express their intended meaning before the live role play begins.

For about 20 minutes, students dig into their mobile phones as tools for looking up vocabulary, brainstorming ideas, jotting down notes on paper or in their devices, in tandem with Internet explorations. There is a humming sense of anticipation, a focus on finding or refining their use of the right words to express their intended meaning before the live role play begins.

Wordless jazz plays out softly from the classroom computer. All windows are open, as 4 of 6 fans buzz and rotate to keep the room cool on another humid morning. The observer chats with a couple of students about what they are learning from the lesson. One is enthused about working on pronunciation and that by having to present three times to peers, it will strengthen the quality of her English speaking. Another sees how both listening and speaking will be used together, in combination with the current task of prepping by writing out ideas for speech.

The teacher is concerned that students not feel rushed, that they have time to think through choices of how to use their English better and in natural ways too. She gives plenty of planning time, and also uses strategies to keep those who finish early occupied. A non-obvious strategy of supporting creativity is consciously deciding to NOT give students an example, feeling that the example could limit their thinking as they would try to follow it.

One challenge to authenticity is that information about 1849 is hard to access. Teacher Praew finds a website about 19th century foods and does some background research on common pathways taken by wagon trains from the East Coast to faraway California. Students of 2020 may not fully grasp factors impacting their role plays, such as weather conditions or the hardships of 19th century travel, such as the inability to preserve foods or saying “goodbye” to family members in the East, not knowing if they would be seen again. However, the lesson’s main objectives are not about history but about giving students a reason to speak in English.

The teacher encourages students during their prep time by chatting with them about their ideas. She writes out simple sentence structures for a couple students who need extra English support. In her low pressure style of meandering around class, she checks in with students, reassuring them that it’s okay if they don’t have all the needed words; she can help. Students had already prepared their posters and another lesson the week before had helped to familiarize them with 1849 historic jargon, so vocabulary phrases and expressions of the era had already been reviewed, building their confidence as they prepared for the morning’s role play.

At 9:53, the time buzzes. “Are you ready?” No, not yet a few students claim. “Ok. I will play one more song, then time’s up.” She pulls up Dan Fogelberg’s long and lyrical “John Sutter’s Mill” song which was introduced the week before, about the California Gold Rush. The teacher sees most students are ready. To stall and give the few remaining unfinished students a little more time, she puts up the day’s riddle:

At 9:53, the time buzzes. “Are you ready?” No, not yet a few students claim. “Ok. I will play one more song, then time’s up.” She pulls up Dan Fogelberg’s long and lyrical “John Sutter’s Mill” song which was introduced the week before, about the California Gold Rush. The teacher sees most students are ready. To stall and give the few remaining unfinished students a little more time, she puts up the day’s riddle:

I’m always in you, I can be on you. But if I surround you, I can kill you.

[What am I?]

The riddle evokes clarification about “surround” as a preposition, a minor distraction. It only takes about 10 seconds before a few students call out “Water.” Then, showing their readiness to move along with the role play, in under 25 seconds the students effortlessly move all their desks and prepare the space for mini-presentations.

Their sales presentations begin. A few students are loud and boisterous, using attention-capturing voices. Others have calm, trustworthy, reassuring voices. It’s their first chance also to see the colorful advertising posters that their friends have made.

“Hello. My name is Earn. I’m the owner of Short River in California. If you want your life to get better, I can help you!” They hear her pitch for travel, and a customer asks, “What will happen if I don’t get any gold?” Earn replies, “I will refund the money to you.” This travel package is only $88 to get from San Francisco to the gold-mining country in the mountains.

In another group, a customer asks, “What is the food?” The quick reply is “anything you want” — “Even if I want lobster?” Too late, she missed that comment as another friend posed yet another question to her. It’s a natural flow of conversation where the focus can shift quickly. It’s a normal flow of real dialogue when several people want answers all at once.

At age 15, students take a wide variety of stances in this authentic-feeling task of creating a company that sells 1849 travel expeditions to far-away California. Some tours go by covered-wagon from Ohio or Boston, others by ship from Tokyo or Bangkok. One magical tour claims to take travelers from Rayong province in Thailand by covered wagon to San Francisco. Some facts seem less important than exploring strategies for making sales pitches today.

Being realistic and creative: In teaching this lesson to six sections of students, after the initial sections early in the week, Praew realized that students were unrealistic about traveling choices in the 19th century. So later in the week, she added the advice that tour packages need to feel trustworthy and reliable for the time period, encouraging students to consider how much time it would take to travel such far distances in the age of covered wagons pulled by horses that get tired after weeks on the road. Earlier in the week when they felt compelled to be less realistic, they were more creative in the breadth of silly yet important questions they asked to friends, being goofy about heating and air conditioning. When more constraints of reality were added, students were a little dull in the range of questions they asked. An inquiry arose: Is it possible for students to be BOTH realistic and creative too? No clear answer came; a teacher can only keep observing, seeing that both realism and creativity are important for the role play task at hand.

Among the tours proposed, the cost of each trip varies from 5 pieces of gold to 300, or $88, or 150 baht for trips leaving from Thailand. Students are adept at asking cost / value questions of what they will get for their money, learning from the questions posed by friends about how far they can push themselves in this role play. If a tour guide offers two horses, an astute customer asks, “What if I need 3 horses? How much extra is that?” Questions about food abound, along with tongue-in-cheek questions of air conditioning in the modes of transportation.

Students enjoy the relaxed role playing atmosphere. By 10:40, their mini- presentations are finished, so Teacher Praew announces: “Ok. Now, you have to vote. Which company will you go with? And give the reason why!” She hands out little white slips of paper. “No names,” she reminds them, so they can cast their votes secretly.

Before the end of each class, Praew reads aloud the ballots. Many have voted to go with the cheaper travel companies, even as Teacher Praew adds playfully, “Cheap, yes. But can you trust this guide?” In one class, a young guide got her imaginary 19th century father to donate a jet for enchanted speed travel from Bangkok to San Francisco and offered the trip for free! In spite of there being no planes in 1849, she wins the day’s light-hearted tour competition. That was the class that motivated the teacher to encourage more realism later in the week.

In another class, there was a 3-way tie, with two trustworthy-sounding tours while the 3rd offered equipment (shovels and pick-axes) that would be made out of gold! For Grade 10 students, playful creativity seems as important to their sense of role play as authenticity. For Teacher Praew, she remains most concerned not about the details of the role play, but what motivates students to engage in a more real English-speaking atmosphere in her classrooms: What feels both authentic and creative to the students?

What do “authentic” and “creative” mean to Teacher Praew?

- An “authentic atmosphere” is one in which language is being used in a real (or life-like) situation or context.

- A “creative atmosphere” implies situations when both the speakers and the audience can ask and answer questions in the moment as they arise.

What do “authentic” and “creative” mean to YOU? How you answer that question should depend on your own lived experience with learning and teaching. There is no single answer.