Choose Your Own Adventure: Building Autonomy Through Story Writing

July-August 2020

Another strategy for building autonomy was an end-of-term “Choose Your Own Adventure” writing project. It also was kept simple, to allow students to feel relaxed and free to make their own decisions. Both strategies involved guided instruction that motivated students to want to be involved and to find out for themselves what they were capable of.

Decision-making in Adventure Writing Projects

Another activity that students liked (as stated by 20-30% in each class according to the survey) was “Choose Your Own Adventure.” This was a few weeks of story writing with other students in mind as their audience. How could they write in a way that would be entertaining for their friends? The autonomy was given through the freedom of developing their own creative storylines, using their own decision making processes for all the elements of the story.

Another activity that students liked (as stated by 20-30% in each class according to the survey) was “Choose Your Own Adventure.” This was a few weeks of story writing with other students in mind as their audience. How could they write in a way that would be entertaining for their friends? The autonomy was given through the freedom of developing their own creative storylines, using their own decision making processes for all the elements of the story.

“Choose your own adventure” is a type of novel in which the author makes “you” (the reader) into the protagonist (the main character) of the story, the actor who makes a series of choices that sends the readers in different directions. It’s like a role-playing type of short story, in which about 8 to 16 different endings are usually possible. Stories can be very simple, or somewhat complex.

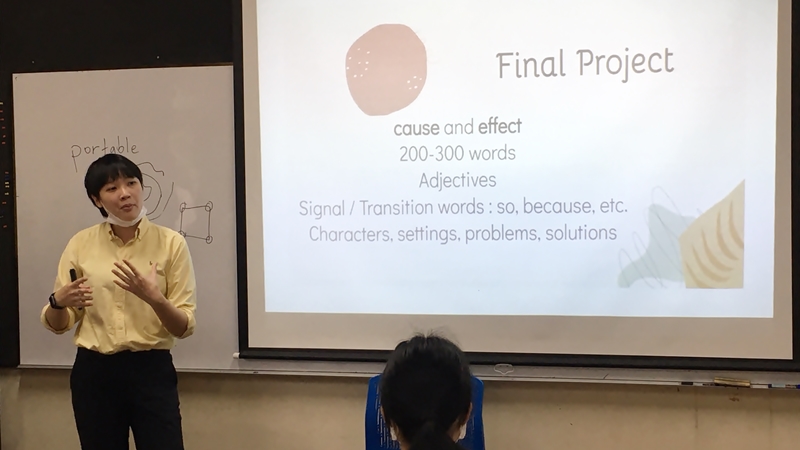

On the first day, for introducing the project, Teacher Praew gives a demo of a short story that she wrote called “The White Envelope.” She reads it aloud: “After a long day at school, you finally arrive at home. Before you walk into your house, you see a white envelope in front of your door.” The first two choices given to the reader are:

- Leave it there.

- Pick it up and open it.

The reader clicks on one choice and moves to the next part of the plot line, getting involved in the choice-making process for how the plot will end.

Teacher Praew shows one more choice, then quickly walks them through three technology options for how they might develop their stories: by video, by Google slides, or by Google forms. Of course, they are told that they can choose any other format too, and later some of them will. “Questions?”

Next she hands out a template of decision points, and shows how she used the chart template to plot out her own storylines toward the story’s different endings. On the overhead projector, she posts five short story ideas for characters and a main plotline:

- A group of children discover a dead body

- A young boy is stuck on the deserted island

- A middle-aged woman discovers a ghost

- A long journey is interrupted by a disaster

- A shy girl unexpectedly bumps into her soulmate

With gentle jazz playing in the background, they focus on developing their initial idea, a mellow atmosphere for thinking through the logistics of their story, step by step. Over the next two periods, students work independently on their projects, at whatever pace and in whatever ways they choose.

With gentle jazz playing in the background, they focus on developing their initial idea, a mellow atmosphere for thinking through the logistics of their story, step by step. Over the next two periods, students work independently on their projects, at whatever pace and in whatever ways they choose.

Just a few expectations are laid out for them: use some new adjectives, check spelling and grammar. In the next lesson, a long list of adjectives gets posted on the board; another day, she shows them an Oxford website of collocations and its practical applications for choosing adjectives. She keeps it very simple, and they stay amazingly engaged, developing most of their own art along the way–some do art by hand, or more often with electronic programs of their choice.

Why did Teacher Praew think that this would be an engaging activity? She explains:

They get to be creative, imaginative — no right or wrong in the story plot or characters. The decision points must simply link. For a few who really have no idea, I may suggest ideas.

Of course, her suggestions are never explicit, keeping opinions to herself, so as to elicit the possibilities from students, let them be the authors of their own stories as fully as they can. For example, one student felt challenged by giving readers a second choice in the plot. Praew’s feedback was simple: Walk the girl through the possibilities in her story: “Think about the reality, if this thing happened, what else could happen?” The question was enough to trigger the girl’s ideas. Triggers for getting their ideas going is all the kids really need, they don’t want the answers; they want to be autonomous but sometimes may simply need a few hints.

How were autonomy and fun integrated in the final project?

Did giving the students a few simple story ideas limit their creativity or their autonomy for making their own decisions? Not too much. Only a few choose the desert island setting, but otherwise most steered clear from the teacher’s example plots altogether. Though, in keeping with preferences of teenagers who need to push on boundaries, they choose many dark topics such as zombies, heartbreak, lost in the woods, living in medieval times with an evil twin sister. Character choices were as varied as their setting choices, and decision-points were carefully contemplated to show how they were thinking about consequences. Good choices did not always lead to good consequences. Many favored bad consequences for most decision points, which may relate to how they perceive reality. Their creative consequences sometimes felt a bit cynical or comical, but in chatting with them about their stories as they were writing, they mostly had a serious attitude of wanting to make something for peers that would be entertaining.

Some were aware of where their ideas came from (“on a field trip last year in Grade 9, I got lost!”), while others were trying to have fun by combining seemingly random ideas into their plot lines and feeling pleased at that. Some were more conscious of the story setting and how that would affect the plot, but no one told them or gave them advice about how to develop their plotlines. They did that all on their own, and the pleasure they took in the creative process itself became palpable in the classrooms, as most students became seriously intent on writing their stories to the best of their abilities.

Some were aware of where their ideas came from (“on a field trip last year in Grade 9, I got lost!”), while others were trying to have fun by combining seemingly random ideas into their plot lines and feeling pleased at that. Some were more conscious of the story setting and how that would affect the plot, but no one told them or gave them advice about how to develop their plotlines. They did that all on their own, and the pleasure they took in the creative process itself became palpable in the classrooms, as most students became seriously intent on writing their stories to the best of their abilities.

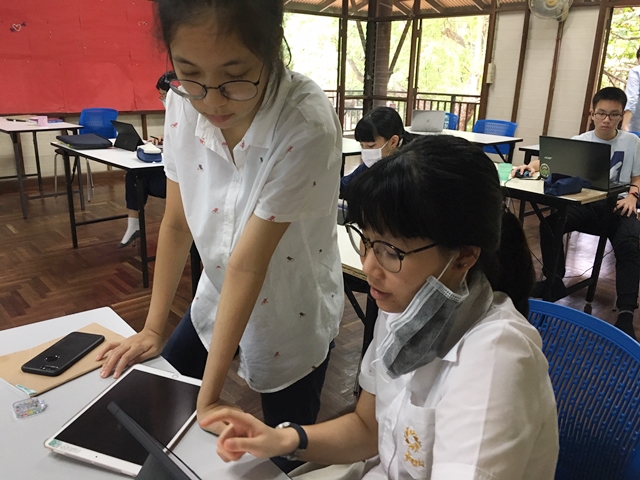

The teacher makes herself available for feedback, but at first students were too engaged in their own ideas and planning to call on her for help. She gets this. Then, when she does help, it’s only as English writing checker, without making comments on their content or plot. Any content goes, no limits on their imaginations: “Don’t want to tell them what I think: Ideas should all come from them.” Admittedly, it’s not easy, sometimes it takes a long time, but she waits patiently. After 3 weeks, every student has a story to share with peers.

In the period just before their final projects were submitted, a clue is given as to how much autonomy is being elicited by students: When two students come at the same time to seek help from the teacher: Instead of reviewing their work carefully, she glances over their stories, notices what verbs need correcting, then sees how the two students themselves could peer correct each other, so she explains how they can work together to help each other, instead of giving the feedback herself.

The seriousness with which the students engage with the final project is common at Roong Aroon, less common at more traditional schools in Thailand. Also, students trust their RA teachers in uncommon ways, and teachers know how to “hold the space” in a non-judgemental, friendly way that stimulates learning.

The seriousness with which the students engage with the final project is common at Roong Aroon, less common at more traditional schools in Thailand. Also, students trust their RA teachers in uncommon ways, and teachers know how to “hold the space” in a non-judgemental, friendly way that stimulates learning.

During the teenage years, students are increasingly ready to assert themselves more into their social world, fewer games (though still some!), more opportunities for direct sharing with some careful planning too. They want to make their own decisions, though many lack confidence, so they push on the doors for greater autonomy. Pushing on their own boundaries, they discover their fuller capacities for both self-direction and leadership too.